November 03, 2010

By Bob Humphrey

Every marked bird carries a story of passage

By Bob Humphrey

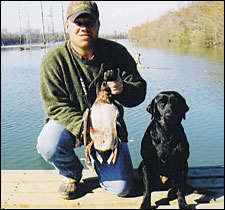

Matthew Finley shot this mallard drake in Stuttgart, Arkansas. It was banded near Houghton, South Dakota, with a standard aluminum band and a green aluminum band worth a $100 reward. |

In the lexicon of waterfowling they're sometimes referred to as jewelry--those bands of silver sometimes sported by our web-footed quarry. That name is appropriate because they denote something rare or unusual. One out of a thousand, maybe far fewer ducks and geese will carry them. They are to the waterfowler what big antlers are to the deer hunter, or long spurs to the turkey hunter: trophies, badges of distinction.

But they are far more than that, for each one has a story to tell. They tie their wearer to a particular place and time, and their recovery is even more revealing for it signifies a journey, a passage.

Last year, Wildfowl invited its readers to share their bands, and the stories of their original owners passages. The response was overwhelming, and far exceeded our capacity to acknowledge all of your contributions. Thus, we felt it appropriate to devote a special feature to the passages, the birds that made them and the hunters who ultimately ended them.

Advertisement

A REWARDING EXPERIENCE

Shooting a banded duck or goose is reward enough, but a few lucky waterfowlers are pleasantly surprised when they find additional reward bands. On the last day of Washington's duck season (01-26-03) Ed Degroot downed a mallard drake that sported two bands. One was a standard, numbered aluminum band. The other was a green aluminum band indicating a $100 reward. Earlier in the season (October 22), Don Davidson (Klamath Falls, OR) also bagged a reward-banded mallard drake. Ironically, it was banded near Lake Klamath, California, and shot in Klamath Falls, Oregon. Maybe the duck got lost and misread the signs.

Those were but a few examples. Others include Richard Carlin (Bicklin, KS), who shot a reward-banded mallard drake last November in Pratt, Kansas, that was banded near Scandia, Alberta. Scott Stewart shot one a year earlier in Fruitland, Idaho, that was similarly banded, a year earlier, in the same location. Ryan Houser (Parker, CO) shot one in Belvue, Kansas, that was banded two days earlier, in Seven Persons, Alberta. Scott Thoele (Fenton, MO) shot one in McCrory, Arkansas, that was banded near East Millis Lake, Northwest Territories; and Matthew Finley (Little Rock, AR) shot one in Stuttgart, Arkansas, that was banded near Houghton, South Dakota.

Advertisement

The purpose of the reward band project is to learn what effect, if any, the switch to phone-in/e-mail band reporting had on band reporting rates. Formerly, leg bands were inscribed with an identification number and a request that the person recovering the band mail the recovery information to the U.S Fish and Wildlife Service. In 1996, the standard aluminum leg bands were changed to carry a toll-free telephone number for reporting band recoveries. Biologists know how many birds of a particular species and population are fitted with standard aluminum bands and with reward bands. By comparing the reporting rates of each, they can assess overall reporting rates for both, then compare those to previous rates to see what effect the switch to phone/e-mail reporting may have had on return rates.

NECK COLLARS

Though they don't earn any cash rewards, another type of jewelry that increases the trophy status of geese is a neck collar. We've received dozens of reports on collars in an array of colors. Anthony March (Markelton, PA) shot a Canada goose in Espyville, Pennsylvania, with an orange collar. Derl Wuertzer (Dubuque, IA) shot a blue goose in Slater, Missouri, with a green neck collar, while his hunting partner Alan Dooley (Dubuque, IA) shot a red-collared lesser snow goose in Triplett, Missouri. And Kelly Block (Breckenridge, CO) shot a Ross's goose with a yellow collar.

Both the colors and the number/letter codes have significance. Yellow and orange collars with three digits are from the Arctic Goose Joint Venture. Large Canada geese typically get four-digit collars of various colors, except in the Atlantic Flyway, where they're fitted with flexible, three-digit "bib-type" collars, which were developed to reduce icing problems for geese that winter in northern areas.

Meanwhile, orange and blue collars are widely used in the Mississippi Flyway as part of an extensive effort to track the populations and movements of Canada Geese. Orange collars are used in the Canadian portion of the flyway and blue collars are used in the U.S. portion. Green collars are reserved largely, though not exclusively for trumpeter swans, and red neck collars have been used on swans, white-fronted, snow and dusky Canada geese.

LONG DISTANCE

Of course one of the main purposes for the banding program is to track the passages of migrating waterfowl, and some of those passages are quite long. From the great state of Texas come several examples. Mitch Bryant (Katy, TX) downed a hen redhead in Hockley that was banded in Mirror, Alberta, and Jeffery Hobday (Temple, TX) downed a lesser snow goose in Collegeport that was banded near Churchill, Manitoba. A Ross's goose banded on the northwest coast of Hudson Bay, Northwest Territories, made it all the way to Pottsboro before Bill Massenburg, Jr. (Denison, TX) shot it. Another contender for our longest trip was a drake mallard that Bill Bird (Edmond, OK) shot at Kaw Lake, Oklahoma. It was banded near Fort Norman, Northwest Territories, and was at least seven years old when it succumbed to a dose of cold steel. Over on the left coast, Paul Mazzilli (Stockton, CA) shot a pintail in Rio Vista, California, that was banded west of Fairbanks, Alaska, and John Meyer (Carmichael, CA) shot a lesser snow goose in Gridley, California, that was banded in Cape Simpson, Alaska. Meyer commented the goose "was skin and bones, no meat at all. Must have just come down from Alaska."

These are just a sampling of some of our long-distance migrants, but provide insight into how season lengths and limits are set. A late spring or a dry summer in northern Canada could profoundly affect hunting conditions in Texas or southern California. Furthermore, those high arctic nesters have to run a gauntlet of guns before they ever reach their wintering grounds.

SHORT DISTANCE

At the other end of the spectrum are our short migrants and residents. Resident Canada geese have become a plague in some areas. However, while their numbers soared, some of the eastern migrant Canada goose populations dropped considerably. Biologists were faced with the challenge of loosening seasons on residents while restricting hunting mortality on migrants until their populations could recover. Band returns were extremely helpful to them in this effort.

We could have devoted an entire "Passages" column to Rusty Martensen of Lanoka Harbor, New Jersey. Last year alone he bagged a dozen banded Canadas in two different New Jersey towns. All were taken either during the early or late resident go

ose seasons, and seven were banded in either New York or New Jersey. He also bagged five banded Canadas the year before in his home state. And Rick Trujillo (Casper, WY) shot a Canada goose that was banded 6/18/1992, four miles north of Casper, and recovered 1/11/2003, five miles west of Casper. That was one old bird.

Over the past two seasons, Rusty Martensen has bagged 17 banded resident Canada geese hunting near his Lanoka Harbor, New Jersey, home. |

LONGEVITY

Speaking of old birds, with all the hunters out there gunning for them, it's amazing the lifespan of some of these birds--something we'd never know if it weren't for band returns. Mallards seem to be particularly long-lived. Gale Johnson (Imperial, NE) bagged a six-year-old and a seven-year-old mallard in Enders Lake, Nebraska. Don Quick (Iron Mountain, MI) shot a seven-year-old drake in Ashdown, Arkansas, and Rick Rose (Amarillo, TX) shot one in Lake Meredith, Texas--his first banded duck.

Moving down the chronological scale, Matt Nard (Rochester, IN) shot an eight-year-old drake in Kipling, Saskatchewan. Scott Setzer (Sacramento, CA) and Frank Rzicznek (Burton, OH) reported nine-year–old drakes in Colusa, California, and Grand River, Washington, respectively. The champion mallard, so far, is a 12-year-old drake shot by Brandon Mase in his hometown of Orland, Indiana. Interestingly, all of these old-age birds were males, which is probably indicative of the higher mortality rates suffered by nesting hens.

Mallards are not the only long-lived ducks though. Ben Fox (Vinton, LA) shot a wigeon drake in Cameron, Louisiana. The band was so badly worn he couldn't make out any of the numbers. So he sent it into the U.S.G.S., where it was treated with acids to recover the numbers. A month later he received a certificate indicating the duck was nine years old. Then, there's Erik Sandsmark's (North Fort Myers, FL) canvasback, which was banded in 1991 in Manitoba and shot last November in North Dakotah; a 12-year-old bird.

A few wary old Canada geese seem to have been able to avoid the gunners for a while too. Jeff Kreit (Baltimore, MD) shot an eight-year-old Canada goose in Fredrick, Maryland, while Doug Fortik (Winnemucca, NV) shot another in Hot Spring Ranch, Nevada. Clare Lyons (Hinton, WV) shot a Canada that was at least 10 in Hinton, a mere eight miles from where it was banded--another resident, perhaps?

Richard Heisel's (Glasford, IL) lucky number must be "11." He shot a banded Canada in Canton, Illinois, 11 miles from where it was banded. It was at least 11 years old and weighed 11 pounds. Jamie Wayland (Standarsville, VA) shot a 12-year-old goose in Standardsville, Virginia. But top honors go to Andrew Rzicznek (Burton, OH), who took a Canada in Mesquito Lake, Ohio, last year that was banded in 1991, and reported to have hatched in 1990 or earlier!

Other geese seem to hold their own in the longevity records as well. Tim Daniel (Pleasant Hill, CA) took a nine-year-old greater white-fronted goose in Swift Current, Saskatchewan, and Dale Richter (Kouts, IN) shot a nine-year-old lesser snow goose in Clay Center, Nebraska. Ralph Nissen (Anoka, MN) shot a 10-year-old lesser snow goose in Churchill, Manitoba, and Chris Burton, (Warrensburg, OH) shot a 12-year-old blue goose in Holden, Missouri.

However, the overall record holder among our "Passages" contributors is Dan Boardsen (Moberly, MO). His lesser snow goose, taken in Simpson, Saskatchewan, in 2002, was banded in 1978 in the Northwest Territories, making it 24 years old. In addition to his certificate, he also received a letter from the biologist who had banded the bird, and has long since retired from the Canadian Wildlife Service. I guess this is proof positive that those mature white geese really are cagey.

ODD DUCKS

Some of the band reports, and the stories that accompany them defy categorization, while others border on "Believe it or Not." For instance, Tom Kowa (Sacramento, CA) shot a female Ross's goose in January 2000, and a neck-collared male in January 2002. Both birds were shot on Pond 6 at Colusa National Wildlife Refuge, and both were banded by the same individual eight years apart.

Mark Johnson (Chippewa Falls, WI) shot two mallards that were banded by the same person, seven years apart. The first, a mallard drake, was shot in Hallie Township, Wisconsin, in 1996. The second, a hen, was shot in Chippewa Falls in 2003. Both birds were banded by Larry Wargowsky, near or on Necedah National, which is roughly 100 miles southeast of Chippewa Falls. Thus, both birds were shot north of where they were banded.

In fact, we've received several examples of birds shot north of where they were banded. Allen Weaver, Jr. (Cedar Rapids, IA) shot a Canada goose in Naicam, Saskatchewan, that was banded in Luverne, Minnesota, and Michael Shafer (Salt Lake City, UT) shot a Canada goose in Outlook, Saskatchewan, that was banded in Ruby Valley, Nevada. Rod Tangeman (Guttenberg, IA) shot a Canada goose in Edmonton, Alberta, that was banded near Bountiful, Utah. The father-son team of Walt and Ken Sharpe, from Ontario, last year each shot Canada geese in their home province. Both birds were banded in Pennsylvania, on different days and in different locations.

While this phenomenon seems a bit odd, there are several explanations. In several cases, the birds were not shot the same year they were banded. It's quite possible they were banded on wintering or staging areas in a prior year, and just never made it back before they were shot.

Birds may also change their migration routes from year to year. Dabblers, like mallards, will pair up on their wintering grounds, and the drakes will often follow their mate back to her natal territory. This could easily lead them to a more northerly area. It might also explain how Mark Johnson (Chippewa Falls, WI) shot a mallard drake in Webster, South Dakota, that was banded in Alburgh Spring, Vermont.

In the case of birds banded and shot in the same year, there is another explanation. Prior to migration, birds sometimes experience migratory restlessness or Zugenruhe, where they'll make short trips, usually in the direction of their eventual trek. They also often congregate in staging areas before setting off on a full-fledged migration. In some instances, these staging areas may be a short distance north of their breeding grounds, which is where most banding occurs.

THE HUNTERS

Sometimes it's the hunters, not the birds, who make the band return so interesting. Robert Taylor (Elyria, OH) shot a neck-collared Canada goose in Carlisle, Ohio, last September, three days before he had bypass surgery--talk about dedicated.

Recent analysis on duck stamp sales has shown a declining number of younger hunters. Our contributors tell a different story though. Jaymz Carriga (Chico, CA) shot a six-year-old pintail the day before his 13th birthday. Fourteen-year-old Storm Chandler (Clovis, CA) shot his first banded bird, also a pintail, last fall in Afton, California. The future of waterfowling lives on.

As you can see, the value and importance of waterfowl bands far exceeds that of mere jewelry. The hunters who harvest birds and report their bands play a vital role in the conservation of North America's waterfowl populations. And the reports not only provide interesting insight into the lives of waterfowl, but also hopefully foster a much greater appreciation for our quarry.

| When It Absolutely, Positively Has To Be Aged Correctly |

|---|

| Bobby Cox's chest freezer worked overtime last year. A waterfowl biologist at the U.S. Geological Survey's Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center, Jamestown, North Dakota, Cox was part of a unique study that asked hunters to ship him frozen duck carcasses, pre-paid via Federal Express, so waterfowl-aging techniques could be evaluated. The project required a full-time phone line and a place to deliver the carcasses day and night, so Cox ran much of it from his house in Ipswich, South Dakota, where 1,200 duck carcasses were delivered. "Whenever our chest freezer got too full, I'd take a load up to the Research Center at Jamestown," Cox remembers. There, the duck wings were separated from the carcasses, with wings tagged and shipped to the Waterfowl Parts Collection Survey centers, also called "WingBees," where duck wings are aged. When duck production is high, more juveniles show up in the harvest, and determining the age ratios within a year's harvest is a key factor in setting hunting regulations for the following season. Yet there were concerns that an error factor in the process might be skewing age-ratios, explains Dr. Frank Rohwer, a study particiapant from Louisiana State University. The study actually began before hunting season, when biologists banded ducks in various locations throughout the prairies and recorded their ages. Hunters who harvested ducks with these special bands and called in their information to the Bird Banding Laboratory, were then asked to call another 800-number. At which point Cox explained the need for the whole carcass and the band. A lot of people warned Cox that waterfowl hunters would not willingly part with their bands. "But I said, 'Yeah, they will. Because they really care about the resource.' And they were really cooperative," shipping 900 mallards, 250 woodies, and 50 teal. After waterfowl hunting season, a WingBee is held for each of the four flyways. The duck wings from this study were sent to each of the WingBees. They were also aged by Rohwer and another biologist with 10 aging processes per wing. This aging was then compared to certain age-revealing internal organs removed from the duck carcasses, plus the aging done by the original banders. The results aren't complete, but so far it's pretty clear that, "The people doing the Parts Survey [aging] are doing a really excellent job," Rohwer says, aging is essentially mistake-free. "It ain't broke, so we don't need to fix it," Cox says, adding, "But you don't know for sure until you look into something like this." --Brian McCombie |