November 03, 2010

By Larry L Reid

The End of One Waterfowling era and the beginning of another.

By Larry L Reid

The interior of Zigrang's general store. Albert Zigrang is on the left. |

The early 1950s were indeed special for a young boy beginning a duck hunting career. I suppose the same could be said about the time your waterfowling days began but the mid-point of the twentieth century was definitely an era that marked an ending of the old, the beginning of the new. For me it was the right time in the perfect place.

My youth saw the last of handmade wooden duck boats, tan canvas coats, paper hull shotgun shells, left over wooden Mason decoys, hard rubber D-2 Olt calls, and Winchester Model 12s and Browning A-5s as guns of choice. Aluminum boats, molded plastic and fiber decoys, stylish camo clothing, plastic hull shot shells, insulated waders, and mass-produced three-inch magnums were all in the beginning stages.

Advertisement

In the '50s, most "kid" waterfowlers were dressed in a Jones style hat, oversized black hippers that usually leaked, and a hand-me-down hunting coat that fit like a blanket.

When removing all the clothes intended to keep you warm, you lost the look of a linebacker, returning to the reality of a growing boy.

Advertisement

Thanks to Dad and his hardcore hunting buddies, my waterfowl journey began on the Mississippi River, upstream of the Winfield lock and dam (Pool 25), on the flooded Batchtown flats; so named for the nearby tiny Calhoun County hamlet in Illinois.

The marsh was a virtual waterfowl paradise, rich in smartweed beds and dotted with family-owned duck blinds.

A day in the blind with those guys was an educational experience and flew by as fast as a green-winged teal. Young hunters were schooled in the ways of a river man, trained in the art of calling and shooting and privy to stories never to be told outside the killing field.

Each hunt was a ritual, almost a religious rite; the boat ride in the dark, precise placement of decoys, toasting the kill, and lastly, the gravel road trip from harbor to the Batchtown tavern where the warriors celebrated the day and relived every shot. That's when I excused myself and headed to Ab Zigrang's General Store.

Mr. Zigrang owned and operated the Batchtown establishment where you could buy shotgun shells, a suit of clothes, and most everything in between.

The Lord only knows what was stocked under the merchandise display tables. Aisles were barely wide enough to walk through and the roll-top desk in the back was as unorganized as a bunch of incoming mallards.

A coal burning "pot-bellied" stove seemed to always glow warm and featured an ancient coffee pot whose contents were strong enough to remove paint.

Zingrang's General Store in Batchtown, IL. |

I didn't go to Ab's store to shop but to hear the tales of a senior river man who was a throwback of yesteryear, the last of the fabled market hunters.

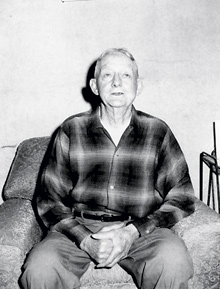

Court was held daily and his yarns focused on the beginning of the twentieth century when the demand for wild game by city folks coupled with a riverman's passion to hunt, gave birth to a select few, the professional waterfowler. In his youth, my white haired friend became a member of this unique group known to the world as market gunners.

Hunting for market had its birth in America in the 1800s on the eastern shore and as the population moved westward, large cities such as Minneapolis, Chicago, and St. Louis became market centers for the selling of wild game.

The ancient Mississippi River system with an ever-present water supply and rich aquatic vegetation always played host to the fall passage and spring return of waterfowl.

Thus, in a time of plenty, before conservation demanded restraint and restriction, there was profit to be made in the sale of wild ducks.

Research indicates that mallards were the bird of choice, selling for as much as $1.25 a pair. A top-notch market hunter had a goal of 100 ducks per day. To reach this lofty mark it took an exceptional person with knowledge, skill, and determination.

With his wiry frame and "damn the torpedoes" attitude, Ab Zigrang, then in his 70s, seemed to possess all the characteristics of a successful market hunter.

Ab loved to talk ducks. |

He once showed me a hand-carved decoy (one of the dozens) set out and picked up daily to lure the bunches in close enough to kill.

Techniques in gunning varied with the market hunters. Many used punt guns mounted on bows of sneak boats, loaded with shot, nails, and shrapnel, fired while aimed into resting flocks of birds.

During Ab's stories, he indicated that his gang thought punts to be not very efficient, as they preferred the Model 12, seven-shot pump gun or extended magazines on Browning A-5s. Either way, "water volleys" were followed by wing shots and hasty cripple cleanup.

His tales featured mass migrations, storms, and slaughter, always ending in detail about the labors of cleaning, packing in salt-laded barrels, and shipping the ducks to the St. Louis market. Hunting for money was a tough task, and many market hunting careers were short lived.

Mr. Zigrang and his partner continued their business, gunning in the late fall, winter and early spring when the abundance of birds and cold weather dictated the requirements to be profitable.

In 1913 the alarm sounded for professional hunters when Illinois reduced the waterfowl season from 225 to 105 days. The elimination of spring hunting spelled the beginning of the end. Then in 1918, the Migratory Bird Treaty Act between the U. S. and Canada brought the curtain down on the era of market hunting and the cast of characters that made its mark in the rich history of waterfowling.

Ab and his cohorts went their separate ways. He opened a store, some b

ecame commercial fishermen, and others sought their livelihood as shellers. They never lost the passion of 'fowling and the story is told that during the dark days of the depression, folks in Calhoun County would find "lots of ducks" lying on their porches, compliments of an ol' market hunter.

Zigrang (middle) with a pile of ducks killed during the Depression. |

These men were not only local heroes--they were legends.

The Batchtown General Store closed in the late 1950's and Ab spent the remainder of his life residing in the storied Whitman Hotel located in tiny Brussels of Calhoun County. On occasion, I would visit my friend and share the sunny front porch of the Wittman, revisiting the past.

I have many reminders of my younger days, but the two favorites are an early hard rubber D-2 Olt plus a photo of Ab on his eightieth birthday holding his gun and limit of mallards taken out of his son Homer's duck hole.

Thanks to the tales and lessons of the old rivermen, the storied tradition of waterfowling lives on for the boys of autumn.