November 03, 2010

By James B. Spencer

Market gunners and early sport hunters required tough breeds.

By James B. Spencer

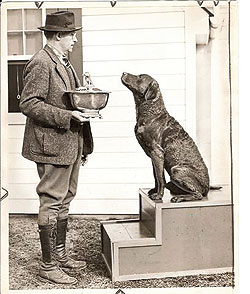

Montauk Pilot, a Chesapeake owned by Bob Carpenter, was Field & Stream's top retriever in 1936. |

The recorded history of waterfowl retrievers in America begins around 1800, and continues through today. However, in a sense, the year 1920 -- right after World War I -- divides the history into two distinct, identifiable periods.

During the first period, American wildfowlers developed four homegrown, regional breeds: Chesapeake Bay retriever, Nova Scotia duck tolling retriever, American water spaniel and Boykin spaniel. In the second period, from 1920 to today, American waterfowlers came to rely more and more on five British breeds: Labrador retrievers, golden retrievers, flat-coat retrievers, curly-coat retrievers and Irish water spaniel. Prior to World War I, these imported breeds had only trickled in.

Advertisement

In Part 1 of our two-part look at the history of waterfowl retrievers in America, we'll cover 1800 to 1920, focusing on the duck dogs of market gunners and early sport hunters. Part 2, in the August issue, will cover the rise of today's popular waterfowl hunting breeds.

Fowling For Food

Through the first period, communications and transportation in America were crude to non-existent. No Internet. No television. Telephones and radios came late and spread slowly, as did automobiles. Early roads were primitive, and improved slowly. Not surprisingly, most folks stuck pretty close to home, whether on their farms or in towns and villages. Even the more adventurous folks who headed west remained mostly in small traveling groups. Our American ancestors lived in small, isolated, tightly knit groups.

Advertisement

Then too, economic conditions were generally quite tough. No 40-hour work weeks, holidays and paid vacations. People scratched long and hard, usually for what we would consider a skimpy living.

Hunting, because it provided necessary food for the hunter and his close kin, was more an enjoyable form of work than recreation. For market hunters, it produced much-needed income.

Where waterfowl abounded, hunters needed either a retriever or a rowboat. Happily for us, many of them preferred to send a retriever rather than to row a boat. But to get a good pup, hunters couldn't just check a few Web sites and make a few phone calls. No, they had to rely on local litters, and they didn't care about pedigrees, as long as the parents were proven retrievers. Thus, in the early years, breeding was quite casual, largely undocumented and highly regionalized.

Of course, over time, breeding became more studied and intentional, and four American regional breeds emerged.

Training was even more casual than breeding. Folks back then didn't have much time to train their retrievers beyond basic obedience. Therefore, they had to develop breeds that would do most of what they needed done with very little training. Of course, dogs with so much natural talent and determination tend to resist extensive training, especially the repetitive drills many rely on today for advanced field trial competition.

Thus, we can call the breeds developed in America during the early years "hunter's dogs," as opposed to the "trainer's dogs" we've imported from Great Britain in more recent years. Let's take a look at each of the four American regional breeds.

The American Water Spaniel began as a local breed in Wisconsin. |

Rise of the Chesapeake

Chesapeakes can be traced back to a pair of Newfoundlands, "Sailor" (male) and "Canton" (female), rescued from a shipwreck off the Maryland coast in 1807. Each became an outstanding retriever on Chesapeake Bay. Although they were never bred to one another, both were bred extensively to other working retrievers thereabouts. Many of their progeny worked out well, so those dogs were bred, both to one another and to unrelated dogs. Down through the decades, few breeders kept records, so we don't know what all went into the development of the breed we now call the Chesapeake.

However, we do know the kind of dogs those hardy souls on the Bay needed and bred. Waterfowl numbers were unimaginable. Legal limits were non-existent. The market for duck and goose meat was insatiable.

Hunters shot a lot of ducks, both for their own consumption and for the market. Clearly, their dogs had to be excellent markers, capable of marking many birds from each flock.

They had to possess great stamina to retrieve dozens of birds all day, every day. Because the Bay's waters could be rough, these dogs had to be large and extremely strong. The water was also quite cold, so the dogs had to have waterproof, well-insulated coats.

Because only such a dog could succeed under those severe conditions, Bay hunters necessarily bred such rough-and-tumble brutes down through those many undocumented decades.

The Chessie has always been territorial and protective. Those traits were bred into him from early on, when he had to protect the boss's property whenever the owner was away, perhaps peddling harvested ducks. Modern breeders have gentled their stock down, but not really all that much.

In 1878, the American Kennel Club registered its first Chesapeake, a male named "Sunday." The current national breed club, the American Chesapeake Club, wasn't formed until 1918. The United Kennel Club recognized the breed in 1927.

The Chesapeake today is still big, strong and tough. The AKC breed standard calls for a height at the withers of 21 to 27 inches and a weight of 55 to 80 pounds. I've seen some out in the marshes substantially larger than that. The double-coat consists of a soft, insulating undercoat overlaid with a harsh, oily outercoat that is practically waterproof.

The color can be anything from dark brown to faded tan (a.k.a. deadgrass).

Strong and tough of body, the Chesapeake is also strong and tough of mind. An excellent marker, he resists interference from his owner, seeming to say, "You shoot 'em without my help and I'll fetch 'em without yours! Understand?"

Granted, field trial/hunting test popularity has forced some breeders to strive for greater trainability, but today's Chesapeake still resists rote drilling.

Not su

rprisingly, as a hunter's dog for the most severe conditions, the "much of muchness" Chesapeake remains supreme.

Tolling Retrievers Serve Double Duty

Originally known as the Little River duck dog, and renamed as the Nova Scotia duck tolling retriever in the early 1920s, this breed is documented back to the early 19th century. The breed almost certainly was known and used long before that. It was originally developed for tolling waterfowl (see sidebar), but has gone on to become both a weatherproof, all-around waterfowl retriever and a flashy upland flusher.

Physically fox-like, the toller stands 17 to 21 inches at the withers, and weighs 35 to 50 pounds. His double coat consists of a warm, woolly undercoat overlaid by a harsh, water-repellent outercoat. The color can be anything from a light gold to copper red. Those who use the breed to toll ducks prize a white-tipped tail, because its flash attracts ducks from a great distance.

The toller is a strong-minded little rascal that resists the repetitive drilling of advanced field trial training. Happily, for the average hunter, he doesn't need it. His small size allows him to fit nicely into the tiniest boat. He's a bouncy, high energy, seemingly tireless worker that will delight any waterfowler, and especially the one who also enjoys hunting upland game birds with a fiery little flusher.

The toller breed was accepted by the Canadian Kennel Club in 1945, but the Canadian national breed club, The Nova Scotia Duck Tolling Retriever Club, wasn't formed until 1974.

In the United States, interest in the breed started in the late 1970s.

In 1984, the U.S. national breed club, the Nova Scotia Duck Tolling Retriever Club (USA) was formed. UKC recognition came in 1987, with AKC recognition in 2003.

Will the toller actually toll ducks today? Yes, wherever ducks are "tollable," which means quiet lakes with reasonably deep water right up to the shoreline, an open shore for tolling retrieves, and cover to hide the hunter. But even where these elements are lacking, the toller is an excellent all-around dog that will do any waterfowl hunter proud.

The Midwest's Duck Dog

We know very little about the origins of this breed. Experts generally agree that Wisconsin market hunters developed the American water spaniel in the middle of the 19th century. But they are less certain about what breeds were used in the process. The breeds most frequently suggested are the extinct English water spaniel, field spaniel, Irish water spaniel, curly-coated retriever and Chesapeake. The AWS became quite popular in the Upper Midwest in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Whatever its origin, the AWS excels as both an all-weather waterfowl retriever and a tireless upland flusher, being equally talented in both types of work.

Medium-sized, the AWS stands 15 to 18 inches at the withers and weighs 25 to 45 pounds. The coat is double, with a soft, insulating undercoat overlaid with a wavy or curly outercoat. The color can be liver, brown or chocolate. Unlike other spaniel breeds, the AWS tail is not docked.

The AWS temperament is uniquely 19th century American: bold, self-confident, fearless, sometimes saucy and truculent, and yet surprisingly sensitive and fiercely loyal. Like the other breeds in this article, AWS is a hunter's dog, not a trainer's dog. He can do most of what the average hunter wants done with just basic obedience training, and he resists the repetitive drilling of more advanced training.

UKC recognition came in 1920. A few AWS fanciers formed a national breed club, the American Water Spaniel Club in 1937. AKC recognized the breed in 1940. However, for many years, AWSC members couldn't agree on whether the breed should be classified as a spaniel or as a retriever, which prevented participation in AKC field trials and hunting tests. Finally, in 2005, AWSC chose AKC spaniel classification, which allowed AWS owners to run their dogs in AKC spaniel hunting tests. Because they can also run them in UKC retriever hunts, they now have the best of both worlds.

How Two Strays Became a Breed

The Boykin spaniel breed began one Sunday morning sometime between 1905 and 1910, when a little brown dog followed Mr. Alec White to church in Spartanburg, S.C., waited for him (some say joined him inside), and then followed him home after church. White kept the pooch, named him "Dumpy," and soon found his little stray could retrieve waterfowl as well as his Chessies.

White turned Dumpy over to Mr. Whit Boykin for further training. Boykin liked Dumpy so well that when he found a similar stray female at the train depot, he took her, named her "Singo" and bred her to Dumpy. The pups worked out well, so the Boykin breed took off and became popular in that region. Over time, other breeds were also used to develop the Boykin, but no one knows for sure what they were. The most likely were Chesapeake, English springer spaniel and American water spaniel.

The Boykin stands 15 to 18 inches at the withers, and weighs 30 to 40 pounds. The breed's flat to moderately curly coat might be any color from solid liver to solid chocolate, with perhaps a white spot on the chest. The tail is bobbed.

The Boykin temperament is all spaniel: friendly, outgoing, eager to please. Like most spaniels, this breed is high-energy, bouncy, and seemingly tireless. Training one is easy, as long as the trainer uses positive techniques. Thus, although it is still a hunter's dog, the Boykin is also something of a trainer's dog, at least for a positive trainer.

The Boykin Spaniel Society was formed in 1977 as both a national breed club and a registry. BSS has resisted breed recognition by other registries. Even so, UKC recognized the breed in 1985. In the 1990s, Boykin owners wanting AKC recognition formed another club, the Boykin Spaniel Club and Breeders Association of America to seek AKC recognition, which came in 2009.

The Boykin is another all-around hunting dog equally capable in retrieving waterfowl and flushing upland game birds.

Invaluable Retrievers

Before World War I, waterfowl retrievers in North America were tough dogs that relied more on natural temperament and stamina than training to earn their place next to duck gunners. While each of the four breeds enjoy a healthy following today, these dogs are no longer the most common canines in modern duck blinds. Still, Chessies, tollers, American water spaniels and Boykins remain invaluable breeds in the history of waterfowl hunting.

James B. Spencer has authored several books on training gun dogs and serves as Wildfowl's "Retrievers" columnist.